Preface:

This is a story about my father’s family improvising, adapting, and overcoming a situation on the farm. It is not untypical of the people of their generation. Their work ethic, family values, and the ability to improvise, adapt, and overcome are the traits that gave them the distinction of the Greatest Generation and they passed that heritage to my generation.

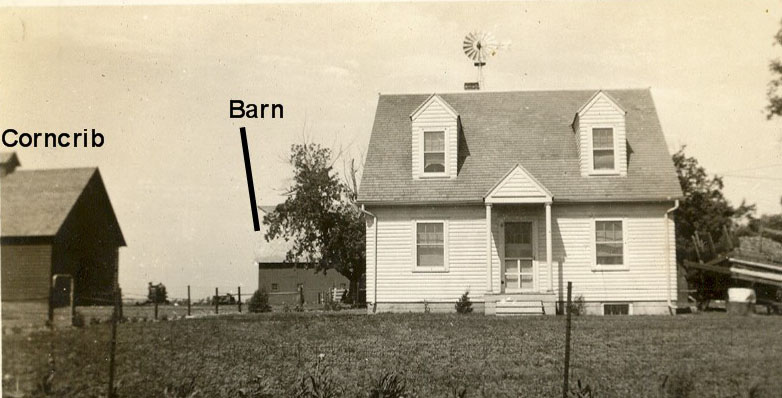

The Crib

The year was 1937. Life on an Iowa farm had been tuff. The country was just coming out of the Great Depression. Winter heating fuel was corn and corn cobs because there wasn’t money to buy coal. The winter of 1936 would be remembered as an epic winter in Iowa. Snow drifts so high that deep trenches were dug by hand to get to the barns and livestock. Roads blocked with deep drifts preventing access to town for weeks. The dust bowl storms and summers of 110 degree days had been common in recent years. The old farm house was in bad shape. The landlord decided to tear down the house and build a new house on the same spot. Great news but where do you live while the house is being built?

The 1930s were among the most difficult years for Americans. The economy had collapsed in the Great Depression. Jobs were scarce, and money was hard to come by. Farm families were in better shape than most because they were mostly self-sufficient. Butchering of cattle and hogs on the farm was still common and provided a supply of meat. Gardens were common, and the vegetables were canned for storage in root cellars for a year around food supply. Heating was supplied by range stoves, pot bellied stoves, or coal burning furnaces. Many farms had a grove of trees the provided wood for the cook stoves. Cutting firewood was a fall ritual. My dad often told stories about the willow row. The willow row was a quarter mile long. The willow trees were cut down with axes and cut up for fuel (chain saws had not been invented). My dad, his brother, my granddad, and great granddad worked their way down the willow row. Great granddad, John, was tall and had long arms that made him an excellent axe man. John enjoyed axe work and made it look easy. Dad always described with disgust that by the time they got to the end of the willow row, the other end was again ready for cutting. Dad didn’t share John’s enthusiasm for axe work. Heat for the house was provided by a coal burning furnace. Some winters they burned wood and corn in the furnace because there wasn’t money to buy coal.

Summers in Iowa are hot. Watch any summer weather forecast in the Midwest and note the record high temperatures. The records were in the range of 100 to 115 degrees and occurred in the 1930s. Air conditioning hadn’t been invented yet. Electrical power was just making its way into the rural areas of Iowa. This farm had electricity and a telephone; both considered luxuries in the 1930s. My dad and his brother cultivated corn at night. A job that was easier during a full moon. The cooler nights were easier on the horses. It was so hot it was not uncommon for a horse to die of heat stroke when cultivating during the day. Farmers with cultivators that required a team of three horses had to be especially careful. The horse in the middle was very susceptible to heat stroke on those hot summer days. Horses were the primary power on the farm in the 1930s. The loss of a horse was a major economic tragedy.

Mechanical power on many farms was limited to a single cylinder hit and miss engine. The engine had a pulley and was connected to tools via a flat belt. The primary tools were a pump jack and a burr mill. The pump jack pumped water from a shallow well to fill livestock water

The 1930s were tuff times in America, but farm families in Iowa were mostly self-sufficient, hardy, and innovators. They were seasoned by hard physical labor and perseverance. Combined with common sense; they were survivors.

The joy of a new house was dampened by the need to figure out where to live during construction. Work on the farm would not cease. The old house had to be torn down before construction could start on the new house. After talking with the carpenters, a schedule was established. The new house could be closed in before winter. The basement could become living quarters for the winter while the house was finished. What to during the summer?

Looking at their resources a decision was made to live in the double corn crib during the summer. The remaining corn could be moved to make room. With a plan, they set out to move everything out of the house and into the corn crib.

The alleyway would be the storage area. One side of the crib would become the kitchen. The other side of the crib would become sleeping quarters for grandma and the girls. Grandpa and the boys would sleep outdoors or in the barn.

The crib was swept and cleaned. The slatted sides of the corn crib were covered with tarps to protect the kitchen and sleeping quarters

The summer was hot but not as hot as previous years. The boys slept outdoors many a night. The family made due with what they had. A new house was worth the sacrifice. Construction was progressing, but the cool days of fall were neigh. The cold nights of early winter on the doorstep when the house was closed in. The family moved into the basement and got situated. They were anxious for the house to be finished.

While all the construction was going on, 10 year old Jeanne had to have her tonsils removed. In 1937 tonsillectomies were not routine surgery. Jeanne’s recovery at home did not seem to be going well. She rested in bed but did not gain strength or energy. She was not in pain but just didn’t seem to be recovering. One afternoon, about a week after the surgery, she started vomiting red blood. Jeanne had been slowly hemorrhaging since the surgery. She turned white as a sheet and was limp. Her dad, Glen, believed in having a phone in the house. The doctor was called, and he wanted her brought to his office immediately. For some reason, the car was gone. Calls were made to neighbors and a car was obtained. Jeanne was rushed to the doctor’s office. The doctor was able to stop the hemorrhage, and Jeanne did recover. The doctor told the family it was a very close call. He thought a half hour later, and he could not have saved Jeanne. But, as the snow flew, the family was thankful to be out of the corncrib and into the warmth of the basement.

The finish work on the first and second floor went well, and they were able to move into the main floor and the upstairs a few days before Christmas 1937. The hardships of the summer had been taken in stride and were now behind them. The joy of the home would be short lived. In 1939 the landlord moved a son-in-law onto the farm and the Stratton’s moved to Milford Township. They moved between Christmas and New Years of 1939. The Nevada School didn’t hold classes on New Years day. Milford school did. Jeanne had to go to school on New Years Day. She was not happy and complained her whole life about it.

REA (Rural Electric Association) electrical power had not yet reached the farm in Milford township. No electricity was just another challenge the family overcame for the next two years. On December 7th 1941 dad was doing the evening milking when the radio announced the attack on Pearl Harbor. Shortly thereafter, his brother Art enlisted in the Army. In March of 1943 my dad married. In October of 1943 Grandpa died. Dad was deferred from the draft to run the farm and care for his mother and two sisters. I was born in April of 1944. In the fall of 1944 the landlord told dad he would have to move. A member of the landlord’s family wanted to farm that land. In December of 1944 we moved to a farm in Grant Township, one mile west of Nevada on Highway 30, and dad remained there until he retired in 1983.

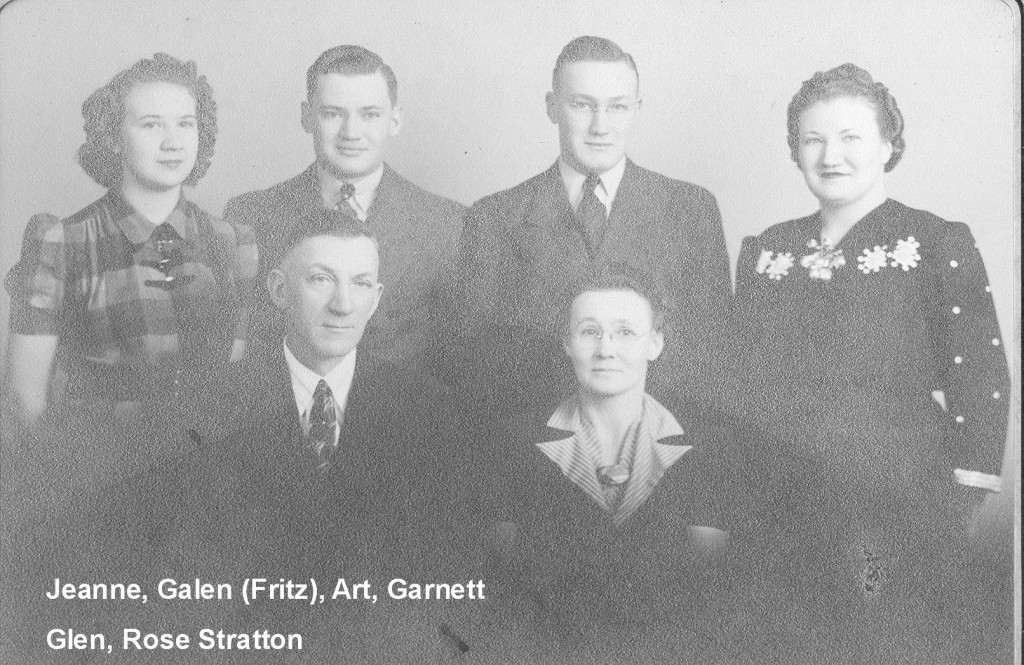

So it’s in our genes. Descendants of Glen and Rose Stratton tend to be self-sufficient, we overcome obstacles, we hate to be told it can’t be done, we have faith in God, as youth we were seasoned to hard work and perseverance, we have common sense, although that was sometimes questioned in our youth, we have strong family ties, and we usually say yes when asked to help others. The hardships in our lives pale compared to those overcome by Glen and Rose. We are what we are because of them and thankful for it.

Postscript:

The house and the crib on this farm were still standing in 2013. Some minor remodeling had been done on the house and the corn crib had been converted to a horse barn. The willow row, the barn, and the rest of the buildings on the farm have faded into history.